The best gift a child can receive

Xinhua News Agency

Updated:2016-02-22

China Daily

The weeks after Spring Festival used to be the most depressing for children left in China's rural areas by their migrant worker parents. The situation is now changing thanks to government moves to provide better-paid jobs in the countryside. Xinhua News Agency reports from Chongqing.

Tao Xingyue, 12, and Tao Junshen, 10, used to dread the end of the Chinese New Year holiday when their parents returned to their jobs in distant cities, leaving the youngsters at home.

This year, though, they had no reason to cry. After five years of living with their uncle in a village on the outskirts of Chongqing municipality, the children have their parents back by their sides.

The Taos were typical of the more than 60 million rural children "left behind" when their parents moved away to become migrant workers. Mother Yu Changmei, a cleaner, and father Tao Yonghong, a security guard, could only return home twice a year from their jobs in Guizhou province.

Now, however, they are an example of an increasingly common type of Chinese family - the reunited ones. Last year, China's migrant population fell for the first time in about 30 years as awareness grew of the risks facing left-behind children. The government is encouraging migrants to return home, partly for economic reasons as it works to close the urban-rural development gap, but also to provide support for lonely children.

A new road map

On Feb 14, the State Council, China's Cabinet, released a guideline on protecting left-behind children, delineating the responsibilities of parents, governments and society at large.

The guideline, signed by Premier Li Keqiang, stated that local governments and village committees should ensure they are well-informed about the conditions faced by left-behind children under their jurisdiction, and to ensure they are looked after properly.

The primary responsibilities of parents were outlined in the document, which also ordered education authorities and schools to ensure that children can live and study in safety.

Local governments are now allowed to use charities and voluntary bodies to provide services for children. A system of reports, intervention, assessment and help will be established, and the guideline also outlined plans to gradually reduce the number of left-behind children.

Two-pronged approach

The document is the first part of a twin approach that will help parents to take their children with them if they leave their hometowns or villages in search of work.

Since 2012, many provinces have gradually revised their education policies to allow the children of migrant workers to take the gaokao, China's national university entrance exam, in cities. That means rural children who would previously have been left at home are now able to live with their parents in cities.

The second part of the approach, being trialed in Chongqing and a number of other cities, is the creation of an improved rural environment that will encourage potential migrant workers to stay in their home areas.

Most residents of Chongqing's outskirts are farmers on low incomes. The municipal government is helping them to start their own businesses from home or to find work nearby.

In the past four years, Chongqing has provided 7.4 billion yuan ($1.1 billion) in low-interest loans to 89,000 migrant workers. Businesses that employ more than 100 ex-farmers can receive subsidies of as much as 600,000 yuan, and 36 industrial parks are offering workshops, entrepreneurial guidance and financing specifically for returned migrant workers.

More than 1.7 million migrant workers have returned to Chongqing since 2010, and more than 30 percent of them have started their own businesses, according to the municipality's human resources and social security department.

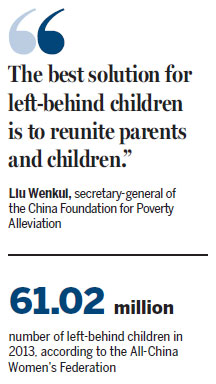

"The best solution for left-behind children is to reunite parents and children," said Liu Wenkui, secretary-general of the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation.

Guan Xinping, a professor of social policy at Nankai University in the northern port city of Tianjin, said a lack of parental interaction could affect children's health and social development.

"The company of their parents is the best gift children can receive. It's not an easy process for an infant to grow to an adult; it requires care and help from their parents," Guan said, adding that parents should engage fully with their children and teach them basic skills, including rudimentary healthcare, housework, communications and morals.

"A lack of this sort of guidance may result in problems," he said.

According to figures provided by the All-China Women's Federation, the country had 61.02 million left-behind children in 2013, with 2.05 million of them living alone without a guardian.

The Zhongmin Academy of Social Protection, a Ministry of Civil Affairs think tank, has released statistics showing that in Guizhou, one of the provinces that feature regularly in lists of children of absent parents, nearly 1.1 million children ages 1 to 16 were classified as having been left behind.

Tragedies

In recent years, a number of tragedies have drawn attention to the plight of left-behind children.

Last year, four children, ages 5 to 13, committed suicide at their home in Bijie, Guizhou, after their parents moved away.

Bijie was also the scene of a horrific crime when a 15-year-old girl and her 13-year-old brother were killed in the family home while their parents were working in a distant province. The police discovered that the girl had been sexually assaulted before she was killed.

In 2014, 10 villagers were imprisoned for repeatedly raping and sexually assaulting a 13-year-old left-behind girl in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

Liu, from the poverty alleviation foundation, said although the cases attracted national headlines, they were quickly forgotten. "The tragedies attracted attention for a while, but became cold quickly. When the news faded, the fundamental problem still hadn't been eradicated," he said.

The scale of the problem has been underlined by surveys and reports compiled by social organizations. A report published in November by the nonprofit Lassock Care Fund of the China Social Welfare Foundation found that girls in rural areas are more vulnerable than their urban peers.

The report said left-behind girls in the country's central and western rural regions face many disadvantages, including inadequate nutrition, poor social development and mental health issues.

Nearly 10 percent live alone without guardians, while more than half stay with their grandparents. Nearly 50 percent of girls left at home have one absent parent, according to the report.

In April, a report on education, led by Zhang Liangxu, deputy director of the China Youth and Children Research Center, concluded that the structure of migrant families is likely to result in juvenile crime.

"There are important links between family factors and juvenile crime. Bad family structure, a lack of parental guidance and a poor economic and cultural environment are key factors that result in delinquent minors," the report said.

Zhang and his colleague Zhao Huijie also conducted a survey at a juvenile detention center.

They found that more than 9 percent of juvenile criminals were left-behind children, while 9 percent were children from migrant families who lived in with their parents in cities.

"The children from migrant families were unable to adapt to the new environment smoothly. When children move to cities with their migrant worker parents, they need to blend in with urban life quickly," Zhang wrote in the report. "However, some children move to the city at a young age and their parents, busy with work, do not provide enough care and attention. Young people may adapt to city life blindly and in the wrong way. On the other hand, the city is not tolerant enough to cuddle these new residents and provide appropriate support."

A high price to pay

It took Yu Changmei three months to secure a job at an electronics factory in Chongqing at a monthly salary of 1,600 yuan, almost the same as she earned in Guizhou. Tao Yonghong has not yet found a job.

Still, they say being a family once again compensates for the drop in income. "It's been worth it," Yu said. "Separation from my family and community was too great a price to pay."

However, the couple didn't return home because they had been persuaded by preferential policies or government aid. Instead, the impetus came from their children's teacher, Peng Kaiqiang, who noticed that the children were often glum and didn't seem to enjoy school parties.

"Their uncle treated them well, and their foster family did not struggle for money. What they lacked was their parents' love," said Peng, who phoned Yu and Tao every week to talk them through the children's academic performances. Eventually, Yu realized the separation was not doing her children any good.

Soon after the couple returned home, Peng saw the Tao children coming out of their shells.

"They used to follow their uncle back home in silence, but now it's all hugs and laughs when their mum or dad picks them up," Peng said.

The parents of some of the other children in the class have also returned home, and the number of left-behind children in the school has fallen to 11 from more than 30 in 2012.

In the past three years, Chongqing's left-behind population has shrunk by 16.8 percent to 890,000.

While this may be good for the children's well-being, the scale of China's migrant worker population nationwide - 247 million at the end of last year, according to the National Bureau of Statistics - means the problem will not disappear altogether.

The authorities are now ready to act on the State Council's new guideline. "Given China's economic and social development, the phenomenon (left-behind children) will persist," said Li Yi, head of children's affairs at the Chongqing Women's Federation.

"We'll help the guardians of left-behind children get up to speed with parenting skills and raise their awareness of safety," Li said. "We've already got 200,000 volunteers ready to offer care and support."

Luo Wangshu contributed to this story.

|

Volunteers play a game with left-behind children at Tangshan Primary School in Xiugu town, Jiangxi province, on Thursday. Hu Chenhuan / Xinhua |

|

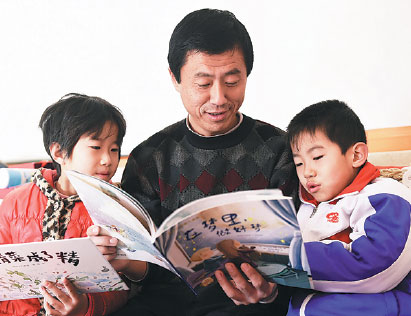

Zhao Wang reads a story to his children at their home in Shijia village, Shandong province, on Jan 27. Zhao returned home before Spring Festival for the first time in a year after working in a city far from home. Dong Naide / for China Daily |

(China Daily 02/22/2016 page6)

Video

John Edwards, the UK trade commissioner for China, praised Chongqing over its rise as a burgeoning center in intelligent manufacturing.